Hurricane Bells

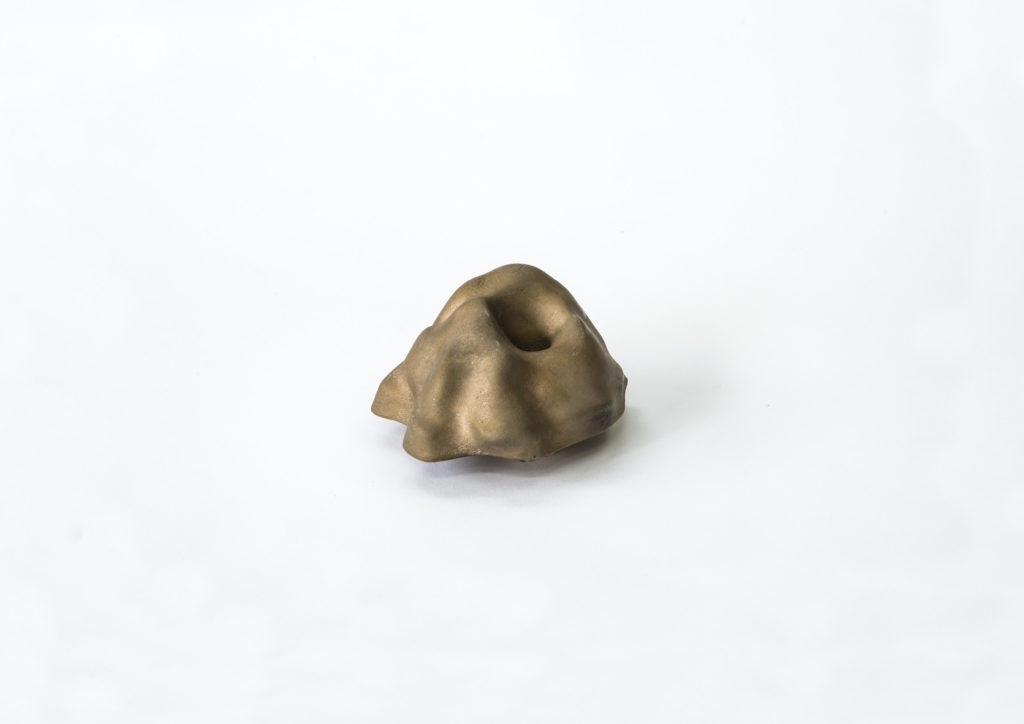

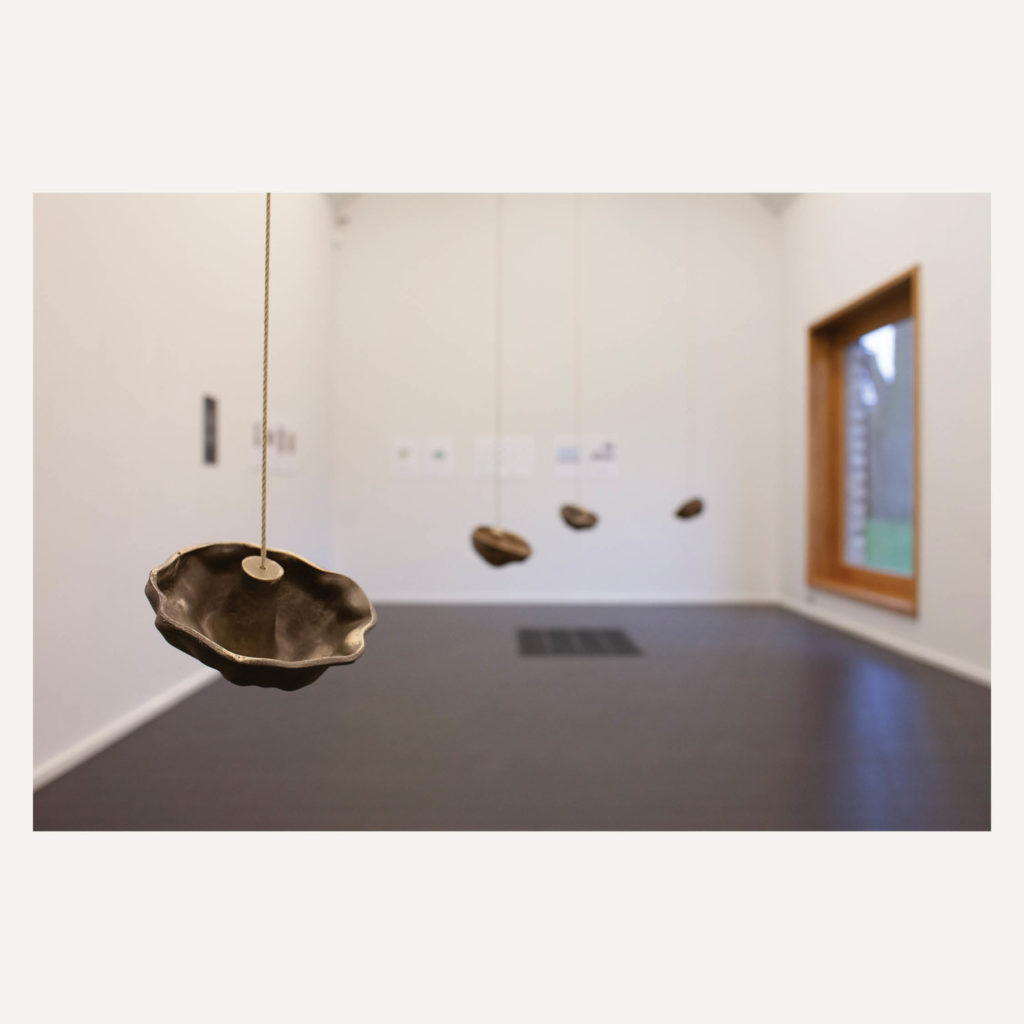

In 2018 I cast five cast bells modeled on the structure of Hurricane Katrina— the storm that devastated New Orleans in 2005. Hung in a line and struck in order, these cyclonic, irregularly shaped musical instruments produce a series of descending tones, indicating the growing power of the storm as it headed across the Gulf of Mexico towards land.

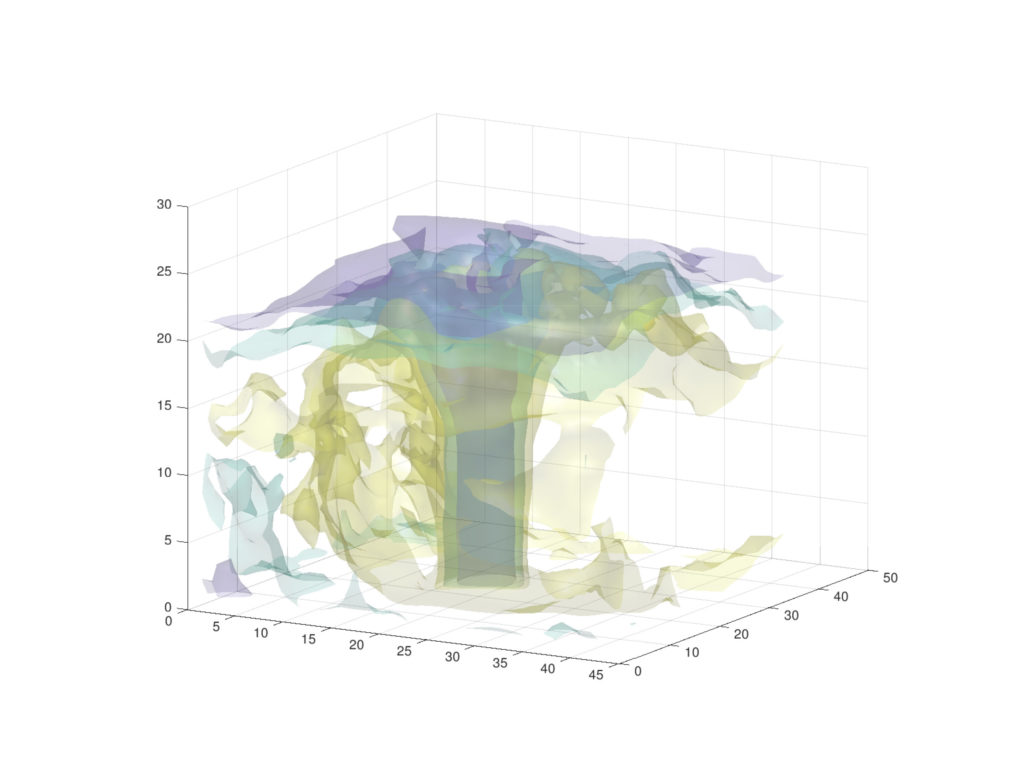

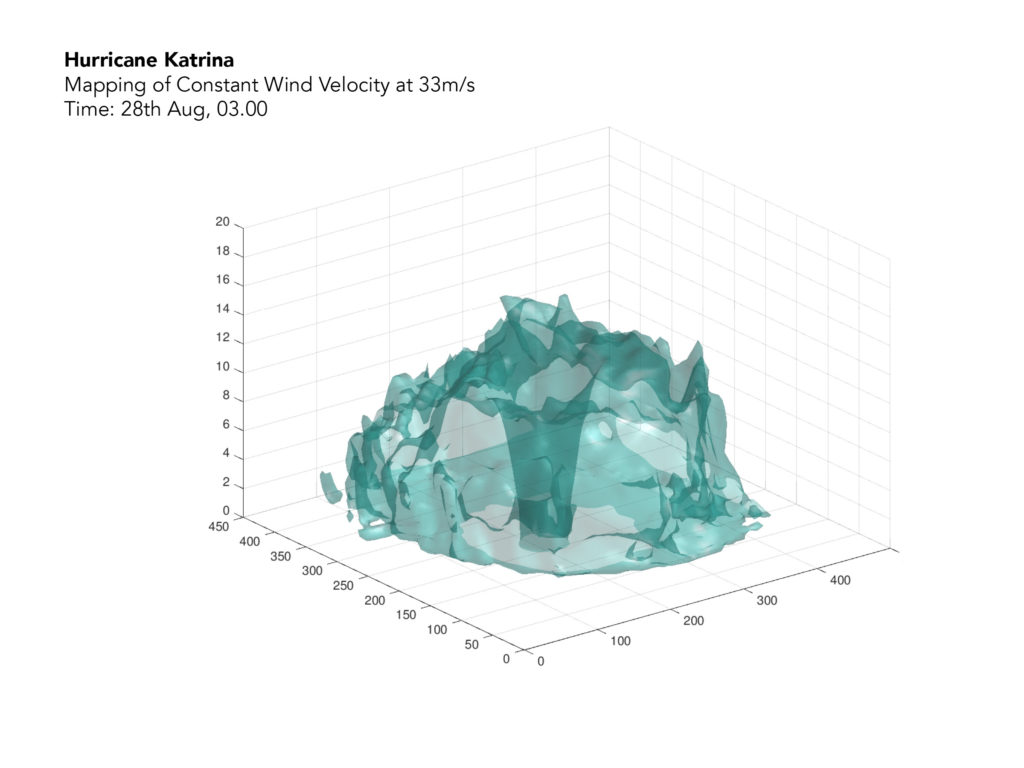

There are many ways to “model” hurricanes, as I learnt in 2018 when I began to research and speak with Dr Carol Corsaro – a climate physicist and hurricane modelling expert from Imperial College London. One way to model a hurricane is to see it like a Russian Doll, comprised of windsheets travelling at different speeds, which are stacked together.

This is the route we chose for that project. I took the windsheet travelling at 33m/s and then played it out over time.

Each bell is a scale model of the storm’s windsheet (travelling at 33m/s) at a particular moment in time, from Bell 1 (an infant storm still brewing out in the Gulf of Mexico) to Bell 5 (a huge cyclonic mass with a depression on one side owing to its collision with the musical city of New Orleans, and surrounding areas).

Roughly speaking, a hurricane’s power grows with its size. So too with bells. Their sound deepens as they get larger. Because of these correspondences, we can therefore “hear” the storm’s progression as we strike the bells in order.

A quirk of the piece is that, once hung, the bells swing freely, and their centre of gravity actually turns them upside-down. I really like the way the imaginary world of data and the tangible world of gravity/weight etc. interplay. It’s important to me that when the bells are shown, people are invited not only to look, but also to play (and hear), and also, to touch, hold them, turn them over, and to use their own bodies to explore their ultimate dimensionality. To hold a hurricane in your hand is a strange experience. Whatsmore, there is something quite nice for me that every encounter between bell and human leaves its mark: through time (over years, decades, longer?) these bells will slowly tarnish, with the salts/water/compounds of the human hand gradually interacting with the bronze, leaving their tarnishing mark on the bells’ surface in an ever-building natural patina (this will affect only the look, but not the sound, of the bells).

In August 2018 the bells were taken to New Orleans to coincide with the thirteenth anniversary of Katrina. Radio 4 conducted interviews with residents and musicians of New Orleans, who struck each bell at the precise moment it represents, sparking wider conversations about the city’s musical identity, memories of Katrina and the aftermath, and thoughts for the future. A 30 minute documentary follows my artistic journey, from conception, design and casting, through to music and responses from New Orleans survivors.

This year I’ll be working with Byron Wallen – a composer and multi-instrumentalist who’ll draw on his incredible ability to combine gong instruments with jazz, classical, and electronic forces. He’s written a piece that focuses on each bell, combining them with some of the noises, sounds, and evocations of New Orleans. This performance is produced in association with Filthy Lucre. We’re hoping to be able to perform in 2021, Covid-permitting….

Why choose bells to communicate data, a story, a storm, a political message?

Bells, and gong instruments in general, have this amazing political and communicative power: they memorialize, they mark celebrations, they sound alarms, they call communities to gather around important issues. There is a set of bells in Myanmar that are used like a musical language, where players hit bells in particular sequences to convey entire sentences of meaning to one another. In Japan they even ring bells to signal incoming typhoons. And the usefulness of a bell in ancient China cannot be underestimated – bells were used as a means of to measure grain for travelling merchants: their cavity was filled with grain, and then the bell was struck and the note it produced was checked against a portable tuning fork to ensure that the merchant’s bell was the correct size.

The story of Hurricane Katrina – and any subsequent climate disaster – demands that we remember and memorialise the dead, the wounded, the displaced. A bell can do this. It can also be an “alarm bell” for future storms, helping to draw attention – and anger, protest, calls for reform – to the “manmade disaster”, as Obama called it, and our current inability to stem our Carbon consumption as a planet (which, in the last few years has seen a larger number of storms of comparable size to Katrina). We must never forget that Katrina was not really a “natural” disaster: it was one of a series of disasters fuelled by climate-denial, structural racism, and woefully insufficient investment, among other factors. The rebuilding effort is still a huge point of contention which shows how these disasters do not simply stay confined to the event of the “storm”.

Alexandra Scott, who played on the bells and who speaks on the radio program, sums it up beautifully:

“I was deeply touched that you’re thinking about us 13 years later. Not to be forgotten is an important thing… We’re all still living our Katrina stories, and this is a form of storytelling. Without storytellers, we’re lost”.

And whilst I worry that we may be increasingly desensitized to imagery of climate disasters I believe that music (and bells) can hit us in a very raw way – they can wake us up to realities we should face. Something of the fact that the Hurricane Bells sound like “something ancient” can, I hope, help to put us in touch with a longer sense of time – a geological time beyond us: many bells, whether they are rung in cities, bell towers, temples, churches, or political buildings have often been ringing for hundreds (even thousands) of years, like an ongoing performance of music spanning multiple generations of players and listeners. This multi-generational attitude is hard to achieve in otherwise fast-paced, present-obsessed time period. Yet the distarstous impacts already accumulating at the door: migrant crises, famine, wars, water shoratges and crop failures, violent weather, death.

The hurricane bells are cast from “bell bronze” – a compound of bronze with a much higher tin content than usual. This compound gives bells (or gongs, or sining bowls, or cymbals etc.….) an unrivalled power to resonate, almost ad infinitum. Yet, bell bronze also has a vulnerability: it’s brittleness. Many European bells – huge, powerful bells – such as Big Ben, Great Tom etc. are cast from this alloy. They are powerful, but they are also vulnerable. This brittleness adds a challenge to the casting process: the metal is heated to around 1100 degrees, and then poured into a cast (bell bronze’s viscosity is comparable to water – the metal can splash and slop around, even though it is many times heavier). Once poured, the metal instantly begins to cool, and as it does so, it is vulnerable to cracking. Any variations in rates of cooling across the metal’s mass will lead to it essentially pulling itself apart, destroying or degrading its resonancy. Therefore, casters must think very carefully about the method of pouring the metal. They must wear not only a musician’s hat, but also, a thermondynamist’s.

The Hurricane Bells were a real labour of love. They failed multiple times before I (and the casters I worked with) got them right. I wouldn’t be surprised if there is some actual blood, sweat, or tears that got mixed into the metal in one of the casts… This wouldn’t be out of keeping with the eclectic methods of monks in some parts of China/Korea/Japan (and beyond I imagine), who apparently throw precious metals into the mix during casting, impulsively heightening the spirituality of the ritual, yet at the same time, destabilizing the process and introducing a further challenge for the casters.)

As mentioned above, bell bronze is also the same material that produced great bells like Big Ben and the Liberty Bell in America. Bells such as these are a reminder that there has also been a more political, perhaps darker, side to bells: bells were, and are, musical instruments of power. Since ancient China, politicans have learnt to use them as tool for subjugation by music – a means to control the public, and even, to subordinate them. The Liberty Bell travelled from the North of America after the civil war touring as part of a larger political project to South, including to New Orleans, proclaiming the new order of the United States. In that day and age it was the biggest bell America had ever seen –a powerful symbol warning southerners to obey. In Britian, Big Ben’s commemorative power is constantly politicised, as with the government’s choice to silence it to mark the funeral of Margerett Thatcher.

In Russia, the meaning and symbolism of bells cannot be overstated. Russia is home to the world’s largest cast bell – the Tsar bell, which was cracked in a fire, and was never rung. Perhaps silent bells have a certain eerie power of political myth-making that cannot be paralleled by their resonant cousins?

The machismo and male peacockery of bell commissions is self-evident in the destructive obsession in size: men (always men, until recently) who looked to fund bells as vanity projects would often insist on hitting their big bells with inadvisably large clappers, against the protestations of the bells’ expert casters. Remember, bell bronze has an almost supernatural quality to ring like no other material, but the price it pays for this is britleness – and no matter how many times casters have painstakingly explained this to bell commissioners, the latter insist on playing bells with over-sized clappers, breaking them immediately…

This happened in the case of Big Ben, whose distinctive clamorous sound today is due to a huge crack in one side, caused by an oversized clapper/ego. Today, Big Ben hangs at the top of the tower of the Palace of Westminster, rotated a quarter turn, so that the (now reasonably-sized clapper) strikes part of its un-cracked surface. (I do sometimes wonder wether the 19th century British onompatepia “BONG” owes its association not merely to bells, but quite specifically, to the broken, utterly idiosyncratic sound of this weird, half-broken bell?)

My bells have also travelled to New Orleans. However, unlike the Liberty bell, nothing is written on them. What’s more, they are tiny – small enough to be held by an individual in one hand and struck using the other hand. With these bells, there was no message I was trying to spread, and certainly no machismo or political order I was hoping to enforce! Instead, I was offering these bells up as a blank slate, a prompt to conversation. New Orleanians who survived the storm struck each bell at the precise time that each bell represents, 13 years to the moment. These people, (so many of them musicians) also played/improvised on the bells, and this sparked conversations about their musical culture, memories of Katrina, and how people survived, and those who were left behind.

On that trip, I like to think the bells acquired new patinas of meaning through their use and interpretation by others. I see Byron’s work as continuing this: he will draw on all of this material, and create something that adds further layers of meaning to the bells through musical exploration of the bells with other instruments.

British navy ships carry an “efficient” bell, for use during heavy fog. A recent tradition has also developed, where the bell is upturned and filled with water in order to be used as a basin for baptizing babies.

Hurricane Katrina, like all hurricanes, first formed out at sea. The reason it incurred a huge loss of life was not merely because of the winds, but because of the subsequent flooding, due to insufficient levy infrastructure.

So water is a crucial part of the story, for hurricanes, and water can play a role for bells too. And so, I’ve begun to try to incproate this element. I’m exploring the sound of the bell being dipped into the water, which produces an effect of bending the note, somewhat akin to the bending of notes in New Orleans blues. Who knows where this might go.

Thanks for reading if you got this far. And thank you to all the people have played and talked about the bells, especially those who shared their stories about Katrina. Your contribution, and your stories mean everything. There is so so much more I want to say, but I’ll stop there, as all stories must stop somewhere.

?

You Might Also Like:

Van Luong (1)

Kjell Zillen (4)

Kjell Zillen (4) Mels Dees (9)

Mels Dees (9) Gao Yu (4)

Gao Yu (4)Katya Lebedev (1)

Juan Dies (1)

Anastasia Prahova (2)

Anastasia Prahova (2)Nena Nastasiya (7)

Taarn Scott (6)

Cynthia Fusillo (20)

Cynthia Fusillo (20)Roberta Orlando (8)

Nanda Raemansky (25)

Nanda Raemansky (25) Eliane Velozo (22)

Eliane Velozo (22)Leyya Mona Tawil (1)

Julia Dubovyk (2)

Jianglong (2)

Iara Abreu (23)

Iara Abreu (23) Agathe Simon (1)

Agathe Simon (1)Rosetta Allan (1)

Elizaveta Ostapenko (5)

Valentin Boiangiu (2)

Valentin Boiangiu (2) Wesley John Fourie (9)

Wesley John Fourie (9) Renato Roque (3)

Renato Roque (3)Rosa Gauditano (5)

Neerajj Mittra (34)

Ciana Fitzgerald (5)

Boris Moz (3)

Katerina Muravuova (5)

Katerina Muravuova (5)Kyla Bernberg (1)

Muyuan He (1)

Muyuan He (1)Liza Odinokikh (2)

Amalia Gil-Merino (2)

Amalia Gil-Merino (2)Paulo Carvalho Ferreira (6)

Anastasiia Komissarova (2)

Anastasiia Komissarova (2) Yumiko Ono (1)

Yumiko Ono (1) Stefania Smolkina (1)

Stefania Smolkina (1)Lena Adasheva (1)

Zahar Al-Dabbagh (1)

Zahar Al-Dabbagh (1) Emily Orzech (6)

Emily Orzech (6) Fernanda Olivares (5)

Fernanda Olivares (5) Noor van der Brugge (3)

Noor van der Brugge (3) Ira Papadopoulou (2)

Ira Papadopoulou (2) Tom Chambers (8)

Tom Chambers (8) Titi Gutierrez (3)

Titi Gutierrez (3) Franz Wanner (2)

Franz Wanner (2) Crystal Marshall (6)

Crystal Marshall (6) Transpositions III (36)

Transpositions III (36) Riddhi Patel (3)

Riddhi Patel (3) Michele Kishita (2)

Michele Kishita (2)Damian Carlton (4)

Deanna Sirlin (1)

Deanna Sirlin (1) Laura Salerno (3)

Laura Salerno (3) Nina Annabelle Märkl (12)

Nina Annabelle Märkl (12) Elina Fattakhova (1)

Elina Fattakhova (1) Tasha Hurley (1)

Tasha Hurley (1) Ian Hartley (2)

Ian Hartley (2) Laurence de Valmy (2)

Laurence de Valmy (2) Ilia Bouslakov (5)

Ilia Bouslakov (5) Andrea Ahuactzin Pintos (4)

Andrea Ahuactzin Pintos (4) Sveta Nosova (3)

Sveta Nosova (3)Carlos Carvalho (1)

Maria Timofeeva (1)

Maria Timofeeva (1) Jinn Bug (2)

Jinn Bug (2) Johannes Gerard (3)

Johannes Gerard (3)Irène Mélix (1)

Aba Lluch Dalena (3)

Aba Lluch Dalena (3) Fabian Reimann (1)

Fabian Reimann (1)Natalia Gourova (1)

Kate Finkelstein (4)

Kate Finkelstein (4)Raina Greifer (1)

James McCann (2)

Naza del Rosal Ortiz (1)

Jay Critchley Jay Critchley (1)

Jay Critchley Jay Critchley (1) Vicky Clarke (4)

Vicky Clarke (4) Maria Silva (4)

Maria Silva (4) Shir Cohen (5)

Shir Cohen (5) Peter Shenai (4)

Peter Shenai (4) Bo Choy (4)

Bo Choy (4)Alina Orlov (2)

Olga Popova (3)

Olga Popova (3) Coco Spencer (2)

Coco Spencer (2) Filippo Fabbri (2)

Filippo Fabbri (2)Daniele Leonardo (5)

SISTERS HOPE (1)

SISTERS HOPE (1) Scenocosme : Gregory Lasserre & Anais met den Ancxt (4)

Scenocosme : Gregory Lasserre & Anais met den Ancxt (4) Anne Fehres & Luke Conroy (6)

Anne Fehres & Luke Conroy (6) Olesya Ilenok (2)

Olesya Ilenok (2) Marie-Eve Levasseur (4)

Marie-Eve Levasseur (4) Natalia Tikhonova (2)

Natalia Tikhonova (2)Ildar Iakubov (1)

Evgeniy Lukuta (7)

Evgeniy Lukuta (7) Jarkko Räsänen (5)

Jarkko Räsänen (5)Maria Guta (6)

Egle Kulbokaite Dorota Gaweda (6)

Thomas Kotik (1)

Andrea Stanislav (3)

Andrea Stanislav (3)Ludmila Belova (1)

Alena Levina (1)

Ilia Symphocat (2)

Ilia Symphocat (2)Yevgeniy Fiks (1)

Star Smart(Formerly Trauth) (18)

Star Smart(Formerly Trauth) (18)Jyoti Arvey (1)

Les Joynes (2)

Ekaterina Ivanova (1)

Ekaterina Ivanova (1) Lev Shusharichev (1)

Lev Shusharichev (1)Michael Stebackov (5)

Ryan Griffith (3)

Lidia Gordeenko (3)

Masha Danilovskaya (7)

Masha Danilovskaya (7) Irina Korotkaya (2)

Irina Korotkaya (2) WagtailFilms Oksana Bronevitskaia&Dmitry Zhukov (5)

WagtailFilms Oksana Bronevitskaia&Dmitry Zhukov (5)Kostya Diachkov (1)

Elena Sokolova (3)

Alexander Nikolsky (2)